Blog

- All

- Beyond The Field

Less Talk and More Action in Treatment Courts

January 29, 2024

Beyond the Field

Treatment Court work is challenging, interesting, and rewarding. However, recovery is a long road, and it can take a long time before participants start to see lasting changes, as they work to acquire essential knowledge and skills. This can be frustrating for everyone. Frankly, all that listening that treatment court programming requires can get a bit, well, boring. What’s the best way to “supercharge” that process? Decades of research supports the Chinese proverb “I hear I forget, I see I remember, I do, and I understand.” The more we can engage participants not just through their brains but through doing, the more likely they are to understand, assimilate, and integrate recovery skills and knowledge. It’s not complicated: “Would you show me how you did that…” “Let’s practice that together…” and “Can you stand up and do…” are the kinds of prompts that ALL members of the team can integrate into their interactions with participants. While therapists are generally tasked with teaching participants essential recovery knowledge and skills, the entire team is responsible for helping to keep those skills active, to provide opportunities for practice and feedback, and to offer encouragement. The payoff is substantial, as research shows that infusing action into our encounters with participants boosts the acquisition of knowledge and use of skills.

Read More

Parenting Adult Children while in Treatment Court

August 25, 2023

Beyond the Field

The negative impact of parental substance use on children’s well-being is well documented within the literature. Family Treatment Courts (FTCs) specifically aim to provide parents involved with the child welfare system with access to clinical treatment and recovery support services in an effort to enhance family functioning and help families stay together and thrive. However, a large percentage of participants in all types of treatment court programs have children (or serve in the role of parent/guardian). As a result, these participants could benefit from enhancing their knowledge and skills within the area of parenting.

Read More

Introducing Our Best Ideas of the Year

July 6, 2023

RISE23 The Best Ideas of the Year The Great Exchange

At RISE23, it was a special time to reflect on the growth and progression in the field of treatment courts through the years. One of the ways that progress comes about is through creative thinking and innovative ideas. While at RISE23, the NDCRC hosted an interactive session titled “The Great Exchange: My Best Idea of the Year” in which we encouraged attendees to share some of their best ideas of the year. This post marks the first in a series of posts sharing the many great ideas that were shared with us. Stay tuned in the following weeks to read about your other great ideas! Let us know what you think about these ideas in the comments, and we encourage you to share your own too.

Read More

Who’s Your Audience? Communicating with Stakeholders to Market Your Treatment Court

April 25, 2023

Beyond the Field

Question: who should know about treatment courts? Answer: everyone, right? While everyone should know about the work and benefits of treatment courts, how we communicate with specific audiences – which we call stakeholders – must be tailored to their role, location, and function. This means that a message to a legislator inviting them to a drug court graduation would be different than a press release announcing the treatment court graduation to the media. The logistical information may be the same but the “so what?” varies across stakeholder groups. According to Ulmer, Sellnow and Seeger (2019), “To communicate more effectively, organizations must determine the types of communication relationships or partnerships they currently have with primary stakeholders.” How do you identify your relationships and partnerships? We can help with that. The NDCRC will be releasing “Marketing your Treatment Courts” in May for Treatment Court Month to help you tell the story of the work of treatment courts.

Read More

OUD, MOUD, & Sleep Disorders

February 15, 2023

Beyond the Field

Statistics

Are you one of the 70 million people in the U.S who experience sleep problems? About one-third of adults get fewer than 7 hours of sleep and report symptoms of insomnia. About 10% of adults at any given time meet the criteria for insomnia disorder, reporting ongoing difficulty getting to sleep, staying asleep, and/or returning to sleep that results in problems with functioning. Another common sleep disorder is sleep apnea (about 10% of adults), in which the person stops and starts breathing again many times during sleep. Sleep apneas can lead to life threatening conditions and requires formal assessment and treatment by a medical provider. As we noted in the Beyond the Field article “Sleep, Trauma and Substance Use,” quality sleep is key to overall health, emotional stability, planning, and sound decision-making. Poor sleep is associated with accidents, heightened pain sensitivity, unemployment, and mental health problems. For treatment court participants, sleep problems can interfere with recovery, making it more difficult to engage in treatment, maintain employment, and use skills to cope with psychiatric symptoms.

People with opiate use disorders (OUD) are at much higher risk of sleep impairments than the general population. Researchers report that as many as 84% of people with OUD experience significant sleep disturbances. Opiate use can create and perpetuate a harmful cycle, in which sleep problems and pain sensitivity trigger opiate use, and opiate use in turn leads to poor sleep and greater pain sensitivity – especially as withdrawal becomes part of the cycle. Furthermore, people with OUD are at much higher risk of not only obstructive sleep apnea, but central sleep apnea when the brain stops sending signals to the muscles that control breathing. This is a condition distinct from the immediate impact on respiration that can follow opiate administration. Studies indicate that about 40% of people with OUD have some form of sleep apnea – four times as many people in the general population. The relationship between OUD and sleep is complex: there are many factors that contribute to poor sleep among individuals with OUD, including co-occurring psychiatric disorders, financial stress, unstable housing, living in unsafe areas, a history of trauma, as well as the use of alcohol, nicotine and other drugs. (Dunn et al., 2018).

Do Medication Assisted Treatments Address Sleep Problems?

While the benefits of medication assisted treatments for OUD (MOUD) are well documented (SAMHSA, 2021), better sleep does not appear to be one of them. Research indicates that sleep does not improve with MOUD. A large study of individuals using methadone found that most reported moderate to severe sleep disturbance at the start of methadone treatment and that their disordered sleep persisted throughout treatment (Nordmann et al., 2016). Likewise, patients treated with buprenorphine did not fare any better in terms of improved sleep (Dunn et al., 2018). Again, the roots of sleep disturbance in OUD are complex. For individuals using both methadone and buprenorphine, psychiatric impairments were the strongest predictor of disordered sleep. Researchers are exploring the ...

Read More

What Treatment Courts Should Know About Sleep, Trauma, & Substance Use

October 19, 2022

Beyond the Field

This is the fifth in our Beyond the Field series of articles that explore trauma and its impact on treatment court work. Treatment court participants can face challenges including complex health problems, poverty, discrimination, substance use, trauma, just to name a few. As a result, poor sleep may not rise to the top of the list of issues to address with individuals. Yet sleep disturbances underlie many of the physical, cognitive, and emotional struggles that can derail recovery. Over 80% of people who have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also have a sleep disorder, and adding substance use to the mix compounds sleep problems exponentially (Vandrey et al. 2014). Recognizing and targeting sleep problems as one dimension of treatment could not only improve health and well-being but may be key to helping people more fully engage in treatment court activities. What are sleep disorders? Sleep is essential to our ability to regulate our mood, make wise decisions, avoid accidents, encode and retrieve memories, and learn new things. Treatment court clients are expected to do all these tasks, and not doing so impedes their progress to graduation and blocks long-term recovery. Not all difficulties with sleep meet criteria for a sleep disorder, but sleep disorders affect people with PTSD at much higher rates than the general population. The most common sleep disorder is insomnia, which includes problems with falling asleep, staying asleep, and returning to sleep after waking. Other sleep disorders that commonly occur with trauma are nightmares and obstructive sleep apnea (Coloven et al., 2018). How are sleep, trauma, and substance use related? The relationship between substance use and sleep problems is fairly well studied, and treatment court practitioners and providers should be aware of the importance of addressing sleep problems within the process of recovery. Use of stimulants, alcohol, opiates (e.g., too much sleep and insomnia rebound), and marijuana withdrawal all can cause or exacerbate sleep disturbance. The self-medication hypothesis is well supported as well, as people who struggle with sleep may turn to substances to help. Much more research is needed to determine best treatment practices, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has published a useful resource to learn more (SAMHSA, 2014; https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4859.pdf) The impact of trauma on sleep is powerful. Re-experiencing traumatic events often occurs in the form of nightmares, and people become hypervigilant, or intensely on guard against future dangers. Depending on the nature of the trauma, people may have come to associate nighttime, darkness, and sleepiness with extreme vulnerability. We are never more defenseless than when asleep, and people who have experienced trauma form negative expectations and cognitions related to the inevitability of future harms. There is growing evidence that PTSD, substance use disorders, and sleep disorders are bi-directionally linked (Vandrey et al. 2014). For example, disordered sleep can make people more susceptible to trauma (e.g. accidents) and more likely to use substances to help them sleep; people with PTSD have symptoms ...

Read More

The What, Who and Why of Trauma-Specific Therapies

July 19, 2022

Beyond the Field

Perhaps you have heard these common misconceptions about trauma therapy for treatment court participants:

- Trauma therapies are too harsh ”they could relapse and they won't graduate.

- Better to treat the substance use first, THEN address the trauma.

- Whatever trauma-focused therapy is available, that will be good enough.

- It is expensive (for providers) to learn trauma-focused therapies, and they are too complicated.

The National Drug Court Resource Center provides free resources to enable treatment courts to implement evidence-based practices and maximize the effectiveness of their programs. In this fourth article in our series on trauma-informed practices, we provide a brief overview of trauma-specific treatments that have the most scientific support, why these therapies are a good fit for many treatment court participants with trauma, and ways to facilitate greater access to these effective treatments.

Importance of integrating treatment for PTSD and substance use treatment

It is well known that trauma and substance use disorders co-occur at very high rates, and treatment courts are well positioned to provide treatment for both, concurrently. This integrated model offers outcomes that are far superior to the outdated, sequential approach that requires treating substance use disorder first, THEN the trauma (Flanagan et al., 2016). Integrated treatment allows clients to address PTSD symptoms that are directly linked to substance use, and vice versa. A sequential model that focuses on treating substance use first reduces the chances that trauma will ever be addressed before the treatment court participant either drops out or completes the program. Providers may fear that clients with PTSD are too fragile in that encouraging clients to face their trauma memories and intense emotions directly could lead to relapse or dropping out of treatment. Conversely, treatment court participants have greater supports and structure in place than in any other time in their lives, so treatment courts are encouraged to take advantage of this window of opportunity.

Trauma-focused therapies with the best outcomes

The following trauma-focused treatments have been rigorously studied and are recommended/strongly recommended by the American Psychological Association and the U.S. Department of Defense (Veterans Services). All are fairly brief (8-16 sessions), and share a direct focus on exposure to memories of the trauma. Some also emphasize changing clients maladaptive beliefs about the trauma and themselves. All the approaches involve temporary discomfort, as distressing memories are activated through exposure (imagined or real-life) and processed in a structured, systematic manner under the direction of the therapist (Watkins et al., 2018). Decisions about which treatment approach is the best fit will depend on nature of the trauma (e.g., combat-related, victim of sexual assault, witness to a violent event), the complexity of the trauma, client preference, and realistically, availability of clinical providers who offer the intervention.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT).People who have experienced trauma try to make sense of the occurrence and can develop distorted beliefs about themselves and the trauma. These stuck points can keep the individual from healing, and include beliefs such as I have myself to blame and as long as I trust no ...

Read More

Trauma-Informed Drug/Alcohol Testing

June 17, 2022

Beyond the Field

This is the third in a series of articles regarding trauma-informed treatment courts. In December 2021, we offered an overview of SAMHSAs (2015) six principles of trauma-informed care and evidence-based strategies for the screening and assessment of trauma in participants. In January 2022, we explored literature on trauma-informed spaces and courtrooms and reviewed findings from environmental psychology. In this edition of Beyond the Field, we review work related to trauma-informed drug testing as it relates to the trauma-informed principles of safety, trust and transparency, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment/voice & choice, peer support, and cultural, racial/ethnic and gender needs.

According to Best Practice Standard #7, Drug and alcohol testing provides an accurate, timely, and comprehensive assessment of unauthorized substance use throughout participants enrollment in the Drug Court (NADCP, 2018, 26). Treatment court teams use drug/alcohol results to monitor participants use of substances to make decisions regarding appropriate treatment services, supervision levels, and the administration of both incentives and sanctions. To this end, the success of any Drug Court will depend, in part, on the reliable monitoring of substance use (NADCP, 2018, 27). Given the vital role of drug/alcohol testing plays within the treatment court environment and the frequency with which participants engage in this program activity (minimum of twice per week during first few months of enrollment is best practice), it is vital that testing protocols are trauma-informed and do not undermine other aspects of the program.

Review of trauma and its associated symptoms. SAMHSA defines trauma as resulting from an event, series of events, or a set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individuals functioning and mental, psychological, social, emotional or spiritual well-being (2014). Because trauma is common among treatment court participants, teams will want to take action to minimize its negative impact on engagement in services, communication, problem-solving, decision making, and outcomes.

Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and related Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) include the following four clusters (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

a) Re-experiencing the traumatic event, or having intrusive, recurring memories or dreams related to the event. Places, sounds, lighting, thoughts, objects, and even words can trigger re-experiencing.

b) Avoidance of situations, thoughts and feelings related to the event. Avoidance symptoms can cause people to resist instructions or escape to safety.

c) Disturbance in arousal and reactivity. People may be easily startled, on edge, irritable, or become angry or aggressive. They may have trouble focusing, sleeping, and paradoxically, may engage in risky or destructive behavior.

d) Numbing and/or other changes in cognition and mood. Numbing, emotional withdrawal or shutdown when triggered, negative thoughts, self-blame, feelings of isolation and apathy are common.

You can probably picture participants who exhibit these behaviors, but might not have considered them to be trauma-related reactions. Trauma-informed courts recognize that the people, places and things embedded in everyday treatment court operations can trigger and exacerbate PTSD and ASD, or even re-traumatize participants. They ...

Read More

Criminals. Offenders. Participants. People.: The Role of Our Beliefs in the Work of Treatment Courts

April 26, 2022

Beyond the Field

(This article is a part of the Connection: The Essential Practice for Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Treatment Courts series.)

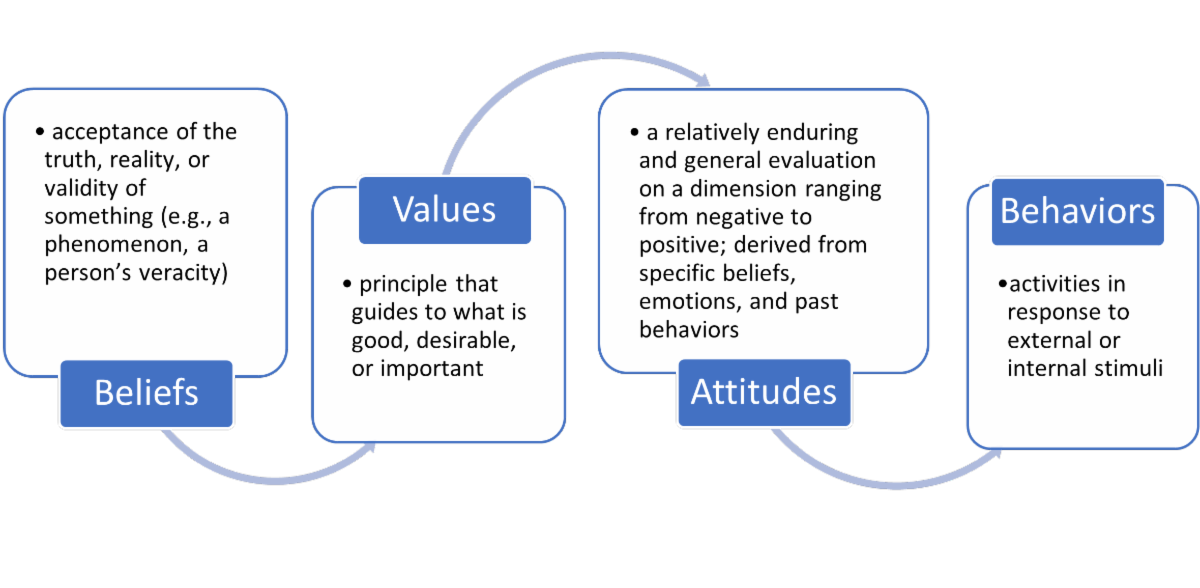

Connection is a through-line in the operating philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence. Yet, the anatomy of connection and that of therapeutic jurisprudence is complex, and precise roadmaps for either are debated among scholars. However, perhaps a helpful framing to best work toward living out this philosophy is to consider four elements: beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviors.

Source: American Psychological Association: https://dictionary.apa.org/

In the last article, the concept of mindfulness was introduced and defined as paying attention to what is happening in this moment, without judgement or reactivity to the thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations that arise (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). As we untangle the anatomy of therapeutic jurisprudence and connection, mindfulness practice allows you to notice what is happening in your mind and body. What thoughts, feelings, and sensations arise when you agree with an idea? When you disagree? Feel bored? When you dislike the idea, have unpleasant feelings, or uncover a judgment of yourself? The foundational skill of mindfulness invites you to stay curious about whatever comes up for you. Curiosity can make way for you to be kind towards yourself and “importantly “ persistent in examining and reflecting upon the ideas ahead.

In unpacking the anatomy of connection and therapeutic jurisprudence, we will first focus on the role of beliefs.

Psychologists define beliefs as the acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity of something, particularly in the absence of substantiation (APA, 2022). Before we examine the role of beliefs in treatment court work, we must first familiarize ourselves with our own thoughts that are pertinent. You are invited to consider the following questions carefully and honestly:

- What thoughts arise when I think about people involved in the treatment court system?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about their motivation, wants, needs, behaviors, capacity for / interest in change, etc.

- What thoughts arise when I think about treatment courts?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about their purpose, design, utility, approach, effectiveness, etc.

- What thoughts arise when I think about my role in the treatment court system?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about your knowledge, skills, preparedness, attitude, motivation, capacity to provide support / make change, desire to help, resources, etc.

Now that you have begun unfolding your own thoughts, we will outline beliefs that therapeutic jurisprudence invites practitioners to try on in treatment court work. These beliefs can include:

- What do we believe about people involved in the treatment court system?

- All people have strengths, gifts, and talents.

- People are not their circumstances, conditions, experiences, or choices. People are in circumstances, experience conditions, have experiences, and make choices.

- People have a complex life story we know only a fraction about. It may include but is not limited to their involvement in the justice system.

- People have needs and wants as well as hopes for their lives.

- People ...

Presence is the Foundation of Connection

March 22, 2022

Beyond the Field

In the introduction to the series, the role of connection to ourselves and others was offered as an essential practice to live out the philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence that underpins treatment courts. But, how do we stay connected to ourselves and others?

Connection requires us to make conscious choices. Active listening, asking questions for understanding, and identifying a participant’s strengths are all examples of choices that can help us stay in connection with others. What keeps us from making these choices? How do we notice when we are in connection, and how do we sustain it? How do we notice when disconnection happens, and then, how do we take steps to reconnect?

The answers to these questions—and ultimately making deliberate choices—first relies on our capacity to notice what is happening in the mind and body. The quality of that noticing—how we do the noticing—is also important to balancing both effective communication with others and taking care of ourselves. The skill that supports us in this is called mindfulness.

What is Mindfulness? (And, What It is Not)

Mindfulness is paying attention to what is happening in this moment, without judgement or reaction to the thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations that arise (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). The practice invites us to adopt an attitude of openness and curiosity about what we are experiencing, with kindness towards ourselves, so that we are able to respond, versus react, to not only what is happening in us but also around us in the environment.

Said another way, mindfulness involves five A’s: attention, acceptance, allowance, attitude, and action (Lee, 2020, 2021):

- Attention: intentional focus to the present moment

- Acceptance: recognition of the truth of what is happening in the mind and body (note: this is not resignation, simply acknowledging what is true at this time)

- Allowance: making space for the full experience of what is happening without pushing it away (unless it is skillful in the moment to have such boundaries)

- Attitude: bringing qualities of curiosity, non-judgment, openness, and kindness to witnessing and holding the inner experience

- Action: choosing deliberative responses (rather than automatic, habitual reactions) that are grounded in awareness of the present moment

Discussion of mindfulness is increasing culturally, which has resulted in the increased accessibility of learning and practicing opportunities. Yet, with the rise of attention to the practice comes, at times, misconceptions. These misconceptions include:

- Mindfulness is about escaping, emptiness, zoning out, or “nothingness.” In actuality, mindfulness is about “falling awake” to the life that you are actually living, versus escaping, numbing, or erasing parts of it (Kabat-Zinn, 2018). Instead, mindfulness is the gentle noticing and befriending of all of the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that make up our inner world.

- Mindfulness is “woo-woo” and is only useful for certain people. Mindfulness is not woo-woo; it is a tradition that spans thousands of years and a variety of traditions. Over the past 40 years, a vast body of research has emerged and bares out the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions for wellbeing in a number ...

Connection: The Essential Practice for Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Treatment Courts

February 16, 2022

Beyond the Field

By design, the judicial system wields disconnection as a tool to gain compliance, police behavior, and execute punishment. Rules are standardized, personal histories often remain unconsidered, change is sought through punitive means, and people are, quite literally, numbers. Arguably, the dehumanization inherent in this approach perpetuates, at least in part, the very social problems it seeks to address.

As a movement, the treatment court model is itself an answer to the ineffectiveness of disconnection in promoting behavioral change for those who experience challenges with substance use and/or mental health. The philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence, which underpins the treatment court model, emphasizes the potential for psychologically healthy outcomes when the legal system is structured as a “restorative, remedial, and healing instrument” (ISTJ, 2022; Kawalek, 2020, p. 2; Stobbs, 2019). Therapeutic jurisprudence is concerned with “the human effects of the law” and the promotion of practices to benefit the “emotional, psychological, physical, relational, economic, and social personhood” of participants (Kawalek, 2020, p. 1-2). Treatment courts offer an important opportunity to leverage the legal system to make meaningful changes in people’s lives.

Collaboration is perhaps the hallmark of treatment courts. In identifying best practices, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP, 2018b) emphasizes the importance of an interdisciplinary approach as well as complementary treatment and social services. Best practice standards also underscore the need for predictability, fairness, consistency, and evidenced-based principles for behavior modification in the operations of treatment courts—practices that cannot be actualized without both interdisciplinary and professional-participant collaboration. The NADCP standards further acknowledge the critical nature of attention to equity and inclusion for participant success; addressing historical patterns of discrimination and inequity certainly requires sincere collaboration (NADCP, 2018a).

The thread of collaboration can be traced back even further to NADCP’s earlier efforts to outline key components of treatment courts. NADCP names the “non-adversarial approach” as crucial to encourage collaborative, coordinated efforts to support participants (NADCP, 2004, p. 3). Another essential component is “ongoing judicial interaction with each treatment court participant,” a standard that explicitly highlights the need for an “active, supervising relationship” in service of increasing the likelihood of participant success (NADCP, 2004, p. 15). Emphasis is placed on early engagement with participants, interdisciplinarity, and “forging partnerships among treatment courts, public agencies, and community-based organizations” (NADCP, 2004, p. 23).

Without question, intentional, focused, collaborative relationships are central to the mission of the treatment court model, and such meaningful collaboration requires connection.

While scholars within psychology offer various conceptualization, social connection may be simply described as a sense of belonging, which can be derived from the experience of acceptance, concern, empathy, and care (Seppala, Rossomando, Doty, 2013). Arguably, a uniqueness of the treatment court model is the opportunity for social connection including

between participants and direct service providers (e.g., case managers, therapists), participants and others professionals (e.g., defense counsel, probation authorities, judges), as well as among the entire team of professionals collaborating with the participant. Notable to the treatment court approach is another, albeit a less obvious, opportunity ...

Read More

Trauma-Informed Spaces and Courtrooms

January 10, 2022

Beyond the Field

When you go into a court you don’t know what’s going on because you’re terrified. There are guns, they’ve got you chained up, and you’re under the influence. All these things are happening at once. — Trauma Survivor (SAMHSA et al., 2013).

People who have experienced trauma can be easily and suddenly overwhelmed, hypersensitive to sounds, confined spaces and objects. They may reflexively respond to these as life-threatening and can’t attend to or remember essential court proceeding or treatment-related information.

The field of Environmental Psychology studies how the physical environment, such as building design, floorplans, signage, and other features of buildings impact our behavior. Designs that provide privacy and a sense of safety are ideally suited for people who have experienced trauma (Garcia, 2020).

Of course, few courts, probation departments, treatment providers, etc. have the luxury of designing their own buildings. However, SAMHSA and other collaborators (2013) compiled tips for treatment court professionals that can help prevent or offset negative impacts of these often-intimidating spaces and promote a sense of safety and respect in participants. They highlight aspects of the physical environment that treatment courts can consider without great expense or delay.

Does your courtroom have seating that provides easy access to aisles and exits? If not, can seats be reserved near aisles? Where does the judge sit? DO they loom above the court, making eye contact and respectful connection difficult? Are people placed in handcuffs and shackled where all in attendance can see? Are the bathrooms where drug tests take place well lit? Is there a space where people can get some privacy if they need a space to calm down? Is the signage posted respectful? OR does it just instruct people what NOT to do?

The article provides a table that describes potential triggers in the environment, the possible reactions of a trauma survivor, and a more trauma-informed approach that treatment courts may take. According to Garcia (2020), “The goal of trauma-informed design is to create environments that promote a sense of calm, safety, dignity, empowerment, and well-being for all occupants. These outcomes can be achieved by adapting spatial layout, thoughtful furniture choices, visual interest, light and color, art, and biophilic design.” It would behoove treatment court teams to assess the physical spaces where participants engage in program-related activities with a critical eye toward minimizing trauma.

Trauma-informed Treatment Courts: Translating Knowledge into Action

December 6, 2021

Beyond the Field

Which clients in your treatment court have a history of trauma? How can you find out? Why does it matter? While the conversation about the prevalence and devastating effects of trauma has become increasingly open in justice settings, many treatment courts may be blind to it in their own programs or simply hope that good intentions will prevent further trauma. Perhaps now is the time to self-reflect as a treatment court and to take small, but meaningful actions right now. According to SAMHSA, “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or a set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being, (2014a, p. 7).” Trauma experiences can diminish the ability of treatment court participants to engage in programs and long-term recovery. So, what does it mean for organizations to be trauma-informed? First, in order for treatment court programs to fully embody a trauma-informed system of care, all program staff must: 1. Have a basic realization of the origins of trauma and the impact this can have on individuals, families, groups, and communities. 2. Be able to recognize the signs of trauma in individuals. 3. Continuously assess the ways in which policies, procedures, and practices should be revised in order to allow staff to respond to individuals appropriately. 4. Resist engaging in action(s) that may result in re-traumatization. In addition, SAMHSA (2014a) identifies six key principles that should serve as the foundation for developing your trauma-informed systems of care. 1. Safety (this is #1 for a reason) – above all else, participants’ physical & emotional safety should be promoted in all settings & through all interactions. Individuals (i.e., staff and participants) who do not feel safe will not fully engage. 2. Trustworthiness & Transparency – treatment court operations should be transparent and conducted with an eye toward developing and maintaining mutual trust between and among stakeholders and participants. 3. Peer Support – incorporating peer recovery support specialists into your treatment court program is an effective way for individuals with lived experience to assist participants in their recovery. 4. Collaboration & Mutuality – recognizing and acknowledging that all treatment court team members and participants have unique roles/responsibilities is key to developing collaborative relationships based on mutuality and respect. 5. Empowerment, Voice, & Choice – treatment court team members look for opportunities to empower participants to make decisions and have a voice in their recovery. 6. Cultural, Historical, & Gender Issues – the treatment court program provides participants with access to clinical and recovery support services that are responsive to their cultural, racial/ethnic, and gender needs. A good place to start moving toward being a trauma-informed treatment court is to screen participants for trauma exposure to determine which individuals are in need of a more thorough assessment and trauma-specific services. Several screening and assessment tools have been validated with justice-involved ...

Read More

Branding Your Treatment Court

November 1, 2021

Beyond the Field

Associating the word “brand” with treatment courts may seem to be a mismatch. Taking a closer look at what branding is, however, opens up possibilities for how we talk about the work of treatment courts with professionals, clients, and the larger community. In communication studies and rhetoric, one of the most prominent scholars who explains narratives and story is Walter Fisher. According to Stache (2017), “In 1978, Walter Fisher proposed a theory of narrative communication, which advances the idea that humans inherently tell stories and like to have stories told to them.” The idea of branding and brands comes from this human need for stories. In the commercial, business-to-consumer sense, brands function as a way for humans to create relationships with consumer goods (Twitchell, 2004). We sometimes call these “brand narratives.” Organizations tell stories in order to gain their stakeholders’ attention and every communication interaction between an organization with its audiences has an impact. In addition, Fisher explains that stories ideally have narrative coherence and narrative fidelity. Narrative coherence means that the story makes sense, and narrative fidelity means that the story rings true to the audience’s experience (Stache, 2017).

What does this look like for treatment courts? It means that the responsibility for communication falls on every member of the treatment court team, because every interaction is an opportunity to create a new reality – a new story – that builds on the mission and vision of your program. Does this mean every interaction must be perfect? Of course not. That’s neither realistic nor human. However, it does mean that open, honest, and authentic communication that aligns with a program’s mission and purpose can create a strong brand story. This strong brand story also means that the inevitable messiness of human communication happens within the context of a coherent story with fidelity. The process of developing your program’s brand can also build goodwill and trust with your intended audience, which will serve you well in times of both crisis and celebration.

How do We Know if a Therapy is Culturally Relevant?

October 1, 2021

Beyond the Field

Innovations like NADCP’s Equity and Inclusion Tool make it easier for treatment courts to “Do Better” to determine if their policies and procedures reduce racial, ethnic, and cultural disparities. But what about therapies? Are evidence-based interventions, say motivational interviewing (MI), equally relevant and effective for diverse populations?

No. The field has been slow to address this problem, but researchers have attempted to adapt existing, effective therapies to make them relevant for diverse clients. For example, Karen Chen Osilla and colleagues developed a web-based MI intervention in English and Spanish to improve the outcomes of Latino first-time DUI clients, (Osilla et al., 2012). They used a strategy called formative iterative evaluation, a multistep process, to assure the MI intervention content and delivery were responsive to linguistic and cultural needs.

First, MI researchers and health literacy experts for Latino & Spanish populations created an in-person MI intervention tailored to first-time DUI clients. Next, they conducted focus groups with clinicians and clients to determine what changes were needed. Then, they adapted the in-person MI intervention to an interactive web format in both English and Spanish. Finally, they tested it again to gather more feedback about its usability and cultural fit.

The developers made changes, such as translating idioms (“getting high”) and adding examples of ways that drinking could negatively affect family and friends. They integrated feedback on social and family values-related themes, adding “drinking with friends” as a reason to drink, “being a good role model” as a reason to stop drinking, and “not meeting family responsibilities or disappointing family/children” as negative consequences of drinking (p. 197). At the final test of the web-based format, clients who spoke only Spanish (compared to English-only and bilingual clients) “reported feeling less embarrassment, shame and discomfort with the web-MI” (p.199).

A later study of the intervention found it was likely not long or intensive enough to make a lasting impact, at least on its own. However, the study provides a sound example of a systematic, collaborative approach to developing effective multicultural therapies. Clearly, treatment court staff and providers cannot afford to wait for intervention research to catch up with the demand for culturally relevant therapies. In the meantime, we can remember that treatments are not “one-size fits-all,” and ask clients--especially those from diverse backgrounds--whether they feel respected, a sense of belonging, and if the therapy is actually helping, throughout their treatment court experience.

Evidence-Based Relationships: The Science of Relationships that Work

September 3, 2021

Beyond the Field

The NADCP Adult Drug Court Best Practice Standards champion the use of evidence-based practices, based on the best available research. While research can tell us what models and interventions work, the how of their delivery is less often discussed. The most effective treatment court teams go beyond the “what” of their program’s offerings (evidence-based practices) and relate to participants in ways that support and promote recovery (evidence-based relationships).

A Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships was formed by the American Psychological Association to analyze the best available research to identify the core components of effective therapy relationships (Norcross & Wampole, 2011). The Task Force concluded that the therapeutic alliance, empathy, and gathering client feedback are clearly linked to positive outcomes. The therapeutic alliance entails mutually agreed upon goals, agreed upon tasks, and a sense of collaboration and relational bond between the two parties. Multiple rigorous studies also indicate that therapists who can express empathy (understand and acknowledge the client’s perspective) and who actively monitor client’s perceptions and responses to treatment are more effective. Relationship behaviors deemed ineffective and potentially harmful include a confrontational style, therapist comments that are hostile or blaming, judging the person versus their behavior, and applying a one-size-fits-all approach that ignores individual and cultural differences.

Relevance to Treatment Courts

While most members of treatment court teams are not therapists, the Task Force’s findings detail what works and doesn’t work in relationships that target lasting personal change. The following can apply to every court team role:

- To enhance the relational alliance, treatment court team members should frequently discuss participants’ personal values and motivations, and collaboratively review program and client expectations.

- While these relationships must remain professional, expressing genuine caring for participants can help form bonds that are healthy, respectful and meaningful.

- Directly asking clients for feedback about the program and their experiences provides opportunities to improve collaboration, to modify approaches as needed, and prevent premature termination.

- Confrontation has historically been a problem in the addictions field. Interactions that are infused with motivational enhancement elements, such as rolling with resistance, reflective responding and active listening serve as antidotes to these all-too-human, but toxic reactions.

- Individualized treatment plans that consider the individual’s unique and diverse identities are a hallmark of treatment court Best Practices, and the Task Force’s findings confirm this. “Fair treatment” does not equal “identical treatment.” It means tailoring the program and services to match the evolving needs of each individual.

Treatment court involvement is essentially a series of human interactions, so relationships between participants and the team are central to recovery. Substance use and criminal behavior can be viewed as rooted in disturbed relationships, disconnection and alienation, and treatment court professionals have the opportunity to make lasting impacts--not only via evidence-based techniques and operational models--but through meaningful, evidence-based connections.

The Science of Conducting Successful Meetings

August 3, 2021

Beyond the Field

How many hours per week do you spend in meetings? Is it time well spent? Do you leave meetings with a sense of a way forward? Frustration? Could your team use a meetings “tune-up”? Workplace meetings are a mainstay of all organizations. For treatment court teams, regular pre-court staff meetings are required as a Best Practice (NADCP, 2018). But teams engage other meetings as well, including those with community stakeholders, program evaluation and planning, and others.

Industrial/organizational (I/0) psychologists Joseph Mroz and colleagues reviewed over 200 empirical studies of meetings in their article “Do we really need another meeting? The science of workplace meetings” (Mroz, Allen, Verhoeven & Shuffler, 2018). They identify worthy goals and provide specific recommendations for conducting successful meetings.

Nationally, they note, the average employee spends 6 hours per week in meetings, and that half of those meetings are rated as “poor” by those who attend. For most organizations, there is a clear need to revisit current practices and consider improvements. Mroz and colleagues identify four primary purposes of meetings:

1) Information Sharing;

2) Problem solving and decision making,

3) to develop and implement organizational strategies, and

4) to debrief a team after particular events.

They recommend that care should be taken before, during and after meetings to facilitate positive outcomes. For example, before a meeting, attendees should have read the agenda, be prepared and arrive on time. The agenda should list clear goals and outcomes and be realistic in terms of allotted time. During meetings, leaders should make the meeting short, and relevant. Humor and laughter can stimulate positive behaviors, but complaining leads to poor performance. Leaders should also intervene when communication becomes dysfunctional or off-track. A clear agenda as described above can go a long way toward mitigating these issues. By the same token, leaders should attend to perceptions of fairness and encourage participation from all attendees. After meetings, effective leaders send out action items and minutes and seek feedback about how others perceived the meeting, to improve the process.

While many of these recommendations seem obvious, researchers have objectively analyzed the costs, interpersonal conflicts, and inefficiencies that arise when these recommendations are not followed. The authors describe a problematic dynamic noted in a study by Simone Kauffeld and Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock, that many readers may find familiar:

When one person starts to complain in a meeting by expressing so-called “killer phrases” that reflects futility or an unchangeable state (e.g., “nothing can be done about that issue” or “nothing works”) other meeting attendees being to complain, which begins a complaining cycle that can reduce group outcomes (p. 488).

This “cycle” is common among professionals in human services fields, and while realism and pragmatism are valuable, pessimism can be contagious and toxic. This is one of the major challenges in treatment court work—even when participants behave in ways that look like “giving up,” staff would do well to convey a sense of hope in how they conduct themselves in meetings.

Microaggressions

July 13, 2021

Beyond the Field

- An African American client stops attending intensive outpatient groups. He explains, “I was the only Black person there-I wasn’t comfortable.” He asks for individual therapy instead but is told “No, group is always best for the intensive treatment people need early in the program. Besides, there is only one race-the human race.”

- A young Latina who is affiliated with a gang is not referred to treatment court, while a young white woman who is also gang affiliated is referred and admitted, “because she’s not as hard core.”

- A transgender client tells her counselor about violence she has faced. The counselor says: “I understand. As a woman, I experience discrimination too.”

Decades of research in cognitive and social sciences show that categorizing, stereotyping, and even discrimination is part and parcel of being a human being. All of us process information and aim to make judgments as quickly and efficiently as possible. We’ve needed to, in order to survive as a species. But a byproduct of this process is that we form implicit biases. Automatic and unintentional, implicit biases are “mistakes” that can lead us to discriminate against others and cause lasting harm.

Microaggressions flow from implicit biases. In the article Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice, psychologist Derald Wing Sue defines microaggressions as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to (marginalized) people,” (Sue et al., 2007; p. 279). The person committing the microaggression can usually “explain it away” by seemingly nonbiased and valid reasons.

Sue and colleagues would consider the first scenario above as an example of colorblindness, or denying a person of color’s racial or ethnic experiences. The message is “You are not a racial/cultural being. You must assimilate/acculturate to the dominant culture.” The second example represents assumption of criminality, when a person of color is presumed to be more deviant on the basis of their race. The third scenario seems well intentioned but reflects a denial of biases. The therapist implies, “Your oppression is no different than mine. I can’t be biased. I’m just like you.” While the therapist is unaware of their mistake, the client feels diminished and misunderstood, adding to their suffering.

Recognizing and confronting implicit biases and microaggressions in ourselves takes courage and humility. Sue and colleagues (2007) offer a model that invites us to be more aware and intentional in each of our personal and professional actions.

Traumatic Brain Injury and Treatment Courts

June 3, 2021

Beyond the Field

A client continually misses appointments, drug tests and curfews. Another has no insight into their problems and repeatedly puts themselves in dangerous situations. Another can’t focus in group treatment and interrupts with off-topic, embarrassing comments. Another is irritable and gets angry quickly. Are these signs of long-term substance use? Mental illness? Traumatic brain injury (TBI)? It could be any and all of these, as they frequently co-occur.

Treatment courts target people with mental health and substance use challenges, but TBI and its long-term impacts are often “off the radars” of court professionals and providers. Lasting effects of TBIs can be easily mistaken for “personality problems” or intense resistance to treatment. The prevalence of TBIs among treatment court clients is unknown, but they are common in the justice system, resulting from accidents, falls, fights, domestic violence, and military service (CDC, 2010).

So, can people with a TBI benefit from treatment court programs? The structure, predictability and case management support that treatment courts provide can make it a good fit, especially if the team is knowledgeable and adapts their practices to meet client needs. Veteran’s Courts are especially aware of these issues, and trainings are periodically offered (check the calendar).

But you don’t need to wait: three online guides for substance use treatment, criminal justice, and mental health professionals are listed below and offer strategies for assessing the impact of TBIs and for adapting daily practices and services. Adaptations include using visual aids, patiently repeating information, slowing down interactions, demonstrating self-regulation skills, and tailoring clients’ environments for reminders. Trauma-informed care in this case requires that teams be aware of the cognitive, emotional and behavioral challenges that can persist well beyond the initial injury, and a willingness to respond with compassion--even though it can be very challenging.

Self Determination Theory and Internal Motivation in Treatment Courts

May 4, 2021

Beyond the Field

Participant #1: “I entered Treatment Court because I want treatment and a better life for my kids and myself.” Participant #2: “I entered Treatment Court because I am sick of jail.” Do clients freely choose to enter a treatment court? The answer is far from simple. Is it a “choice” when the criminal justice system relies on external motivators like incarceration and resulting cascade of losses? Ideally, the choice to enter a treatment court would be an autonomous one that reflects a participant’s internal motivations to live a healthier, more meaningful life. Deci and Ryan’s Self Determination Theory (SDT) holds that internally motivated behaviors are stronger, longer lasting, and produce better outcomes than those that are externally motivated (Deci & Ryan 1985). SDT provides the framework for a number of studies of the impact of treatment courts and other legally mandated programs (e.g. Morse et al., 2014; Wild et al., 2016). According to SDT, three psychological needs must be met to foster internal motivation and self-determined behavior: Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness. To the extent that treatment courts support these inborn, intrinsic needs, clients are more likely to engage in treatment and maintain gains. Autonomy is enhanced when clients feel they have options and take responsibility for choices. At intake, staff must make clear the voluntary nature of treatment court programs, especially because the consequences of refusing are often swift and aversive. Does the court notice and consistently praise and encourage values-driven choices, or does it emphasize missteps and sanctions, which detract from autonomy? Motivational Interviewing is a NADCP Best Practice designed to maximize autonomy and minimize coercion. Competence develops through a focus on skills development, repeated practice, and environmental support. Evidence-based practices such as relapse prevention training and stress management equip clients to face the challenges of recovery. Lapses are viewed as opportunities to refine skills and increase competence. Relatedness is the need to interact and be connected with others. Through treatment groups and treatment court membership, clients give and receive support, which is both healing and crucial to problem solving and competence. While Client #1 seems more internally motivated and ready to engage, research indicates that Client #2 also has the potential to succeed in treatment court. SDT holds that over time, externally motivated behaviors can transition to become internally motivated. This process is at the heart of therapeutic jurisprudence.

Read More

The Neurobiology of Substance Use Disorders

April 5, 2021

Beyond the Field

This month, NDCRC Director of Clinical Treatment and UNCW professor of psychology Dr. Sally MacKain discusses how an understanding of the neurobiology of substance use disorders can inform treatment court practices. Treatment court clients struggle with significant cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social problems. Understanding some basics of the neurobiology behind these difficulties may help court team members tailor their interactions and services more effectively. Dr. MacKain breaks down the article Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction by Nora Volkow, George Koob & Thomas McLellan (2016) which reviews scientific evidence supporting the view that substance use disorders are rooted in changes in how our brains are structured and function. The authors contend that a brain disease model of substance use has facilitated a movement away from shaming, stigma and incarceration. Volkow and her colleagues have made an important contribution in helping those of us who are not brain scientists understand more about the neurobiological changes associated with substance use disorders, how a disease model of addiction fits the evidence, and why recovery can be so challenging.

Read More

The Science of Future Thinking and its Role in Recovery

March 1, 2021

Beyond the Field

Would you prefer a delicious piece of chocolate now or a whole chocolate bar tomorrow? A 3-day vacation now or a 7-day vacation in 5 months? To spend an extra/bonus $500 now, or put it in a savings account to accrue interest? Most people prefer immediate rewards over delayed ones. However, people with substance use challenges tend to find it especially difficult to imagine their futures and delay rewards. Research indicates that people with substance use disorders have a narrower temporal window, meaning their attention is focused on gaining near-future rewards, such as the next drink or next drug use opportunity. For example, studies show that when asked about their own future, the typical individual reports goals and activities about 5 years in the future. In stark contrast, people with heroin use disorders offered reports that extended only 9 days in the future, on average (Patel & Amlen, 2020). Delay discounting is the term used to describe the rate at which future rewards are less valued over time. Higher rates of delay discounting are related to impulsivity and risky behaviors like drug and alcohol use. Research in Episodic Future Thinking (EFT) suggests that helping people to vividly imagine personally salient future events could help them learn to delay rewards in order to get a bigger payoff in the longer term (Bulley & Gullo, 2017). Applied to a treatment court context, clients could learn to forgo short term rewards such as relief from craving or feeling euphoric, in favor of long-term goals, like graduating from the program, freedom from probation, and regaining custody of children. Several promising studies of EFT with people with alcohol dependence show positive results. For example, Snider, LaConte & Bickel, (2016) encouraged participants to expand their temporal windows by thinking about personally relevant future events and describing them in salient detail. Participants reported the most positive event that could realistically happen at each of 5 points in the future (1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 1 year). Researchers then probed: What will you be doing? Whom will you be with? Where will you be? How will you be feeling? What will you be seeing? What will you be hearing? What will you be tasting? What will you be smelling? (pp. 1160-1161). They also asked a comparison group of people with alcohol dependence to imagine PAST events in the same timeframes, with similarly worded probes. This method allowed researchers to assess the unique contribution of a future time orientation. Each participant's future or past personalized account was then integrated into a task in which they chose between hypothetical gains in money received now or after some delay (e.g., Would you like $50 now or $100 in a year? They also administered measures of alcohol use. They found that over time, people in the future-thinking/EFT group came to value future monetary rewards more highly and reduced their alcohol consumption. These improvements were also found in a study that involved a one-week, 4-session/practice protocol ...

Read More

Compassion Fatigue

February 3, 2021

Beyond the Field

Compassion is defined as “the ability to understand the emotional state of another person or oneself…and a desire to alleviate or reduce the suffering” (Engel, 2008). Given that treatment courts are an application of therapeutic jurisprudence (see Winick & Wexler, 2015) and seek to facilitate the rehabilitation process, all team members (e.g., prosecuting attorneys, defense attorneys, law enforcement representatives, case managers, probation/parole agents, etc.) should display compassion when interacting with participants.

We know that the work of treatment court practitioners can be both rewarding and challenging. On one had treatment courts facilitate change within individuals who may have repeatedly cycled through the criminal justice system. However, asking team members to embody principles of therapeutic jurisprudence generally and compassion more specifically may run contrary to previous schooling and/or training. For example, Norton, Johnson, & Woods (2016) highlight the challenges lawyers may experience given their law school training (e.g., Socratic method) and the structure of the legal profession (e.g., adversarial system). This reality underscores the need to be mindful of a phenomenon titled “compassion fatigue” (or secondary trauma). Compassion fatigue has been defined as “’the cost of caring’ for those in professions that regularly see and care for others in pain and trauma” (Grant, Lavery, & Decarlo, 2019:1).

Dr. Françoise Mathieu’s TEDx Talk “The Edge of Compassion” addresses strategies for sustaining both compassion and empathy for others.

In order to maintain fidelity to the treatment court model, it is imperative that all team members are operating in accordance with the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence and are mindful of how compassion fatigue (or secondary trauma) manifests itself and what it “looks” like. This level of awareness among treatment court practitioners will allow for course correction should they experience the “psychological and physical effects of exposure to the pain, distress, or injustice suffered by clients” (Norton, Johnson, & Woods, 2016:988).

According to Lee & Miller (2013) “Self-care has been described as a process, an ability, but most often as engagement in particular behaviors that are suggested to promote specific outcomes such as a ‘sense of subjective well-being’, a healthy lifestyle, stress relief, and resiliency for the prevention of empathy fatigue” (97). They go on to describe two distinct, but inherently connected dimensions of self-care; personal and professional. Personal self-care focuses on holistic health and well-being of oneself, where as professional self-care “is understood as the process of purposeful engagement in practices that promote effective and appropriate use of the self in the professional role within the context of sustaining holistic health and well-being” (98). Lee & Miller argue that both dimensions of self-care must be cultivated in order to develop and maintain a healthy and resilient workforce. So, what is needed in order to fully develop personal and professional self-care? What specific areas of one’s personal and professional life should be considered and supported? Lee & Miller (2013) identified several areas within both dimensions which are outlined in Table 1 below. A specific discussion of ... Self Care

January 8, 2021

Beyond the Field

The term “self-care” has been used by scholars and practitioners across many disciplines (e.g., social work, psychology, nursing, education, etc.) as an identified strategy for bolstering health, well-being, and resiliency among members of their respective workforces. Despite this and the increasing discussion of self-care within the larger society, minimal consideration has been paid to the role of self-care in providing these same benefits to practitioners within the criminal justice system and specifically treatment courts. This is an obvious oversight and an area in need of empirical focus given the nature of work performed by criminal justice system and specifically treatment court practitioners. According to Lee & Miller (2013) “Self-care has been described as a process, an ability, but most often as engagement in particular behaviors that are suggested to promote specific outcomes such as a ‘sense of subjective well-being’, a healthy lifestyle, stress relief, and resiliency for the prevention of empathy fatigue” (97). They go on to describe two distinct, but inherently connected dimensions of self-care; personal and professional. Personal self-care focuses on holistic health and well-being of oneself, where as professional self-care “is understood as the process of purposeful engagement in practices that promote effective and appropriate use of the self in the professional role within the context of sustaining holistic health and well-being” (98). Lee & Miller argue that both dimensions of self-care must be cultivated in order to develop and maintain a healthy and resilient workforce. So, what is needed in order to fully develop personal and professional self-care? What specific areas of one’s personal and professional life should be considered and supported? Lee & Miller (2013) identified several areas within both dimensions which are outlined in Table 1 below. A specific discussion of each area of attention and support is provided in the journal article. Go check it out!

Read More

Therapeutic Jurisprudence & Empathy

November 30, 2020

Beyond the Field

It is widely acknowledged that therapeutic jurisprudence serves as the theoretical foundation for the treatment court model. This perspective “seeks to assess the therapeutic and anti-therapeutic consequences of law and how it is applied. It also seeks to affect legal change designed to increase the former and diminish the latter.” (Winick & Wexler, 2015, p. 479). Treatment court scholars and practitioners recognize that treatment courts stand in stark contrast to traditional criminal courts in how they are structured as well as how they operate. Winick & Wexler (2015) assert that “an important insight of therapeutic jurisprudence is that, how judges and other legal actors play their roles has inevitable consequences for the mental health and psychological well-being of the people with whom they interact.” (p. 481) One strategy for putting therapeutic jurisprudence into practice is through the practice of empathy. Empathy is defined as “the ability to see a situation from someone else’s perspective—combined with the emotional capacity to understand and feel that person’s emotions in that situation.” (Colby, 2012, p. 1945) Drug Court Key Component #7 & Adult Best Practice Standard #3 highlight the critical role of judges in treatment courts and specifically the interaction between judges and participants during court review hearings. More specifically,

Read More

Judges…need to understand how to convey empathy, how to recognize and deal with denial, and how to apply principles of behavioral psychology and motivation theory. They need to understand the psychology of procedural justice, which teaches that people appearing in court experience greater satisfaction and comply more willingly with court orders when they are given a sense of voice and validation and treated with dignity and respect. (Winick & Wexler, 2015, p. 482)

While judges are integral to the success of any treatment court program, less is written about the specific role of other interdisciplinary team members (e.g. prosecuting attorney, defense attorney, case manager, law enforcement, etc.) in adopting the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence in their work. It is vital for all treatment court team members to practice empathy when interacting with program participants. The below-listed multimedia resources provide some additional insight into how to practice empathy within your work as a treatment court practitioner. According to scholar Jamil Zaki “empathy is like a skill. It's like a muscle. We can practice it like any other skill and get better at connecting with people.” (Young, 2020) Developing Good Habits

November 25, 2020

Beyond the Field

According to Knottnerus (2005) “. . . daily life is normally characterized by an array of personal and social rituals. Such rituals help create stability to social life while expressing various symbolic meanings that give significance to our actions” (p. 8). Both positive and negative behaviors are part of daily life and when practiced often enough become ritualized. Individuals in recovery often report that certain “people, places, or things” can elicit behavioral responses without conscious awareness or intention. This reality underscores the need for the recovery process and programming to include an emphasis on individuals recognizing negative rituals and replacing them with positive (or prosocial) rituals. We know from research that this behavioral change must be predicated on a change in attitudes/beliefs, an increase in knowledge regarding the behavior and associated consequences, as well as ample time to practice new behaviors within a structured and supportive environment. Changing ritualized behavior can be a difficult process and feel very foreign no matter how positive the results may be. Researchers, Van de Poel-Knottnerus and Knottnerus (2011), assert that “. . . when patterned, ritualized modes of behavior are severely disrupted, this is a very difficult and problematic situation for human beings” (p. 108). To this end, understanding how ritualized behavior forms, as well as how it can be effectively changed, is central to the work of treatment court practitioners and researchers. Understanding the specific mechanisms by which programs affect behavior change among various target populations, and sub-populations, is crucial to success and sustainability.

Read More

The Importance of Social Connectedness

November 9, 2020

Beyond the Field

The importance of social connectedness among human beings has been well-documented. Researchers have found physical, emotional, and social benefits for individuals who are and remain connected to others. These same researchers have found profoundly negative outcomes associated with experiencing social isolation.

In these current times, the methods by which individuals connect with each other have taken on multiple forms (e.g., face-to-face, by phone, via cloud-based technology, etc). How is this notion of social connectedness relevant to the treatment court field? It is hoped that the information presented in the multimedia resources featured here will encourage you to examine the ways in which your treatment court program facilitates meaningful social connection between and among participants, team members, and the recovery community through program requirements (e.g., case management sessions, pro-social activities, court review hearings, etc.). It is vital that opportunities for participants to connect with others are maintained.

Read More

In these current times, the methods by which individuals connect with each other have taken on multiple forms (e.g., face-to-face, by phone, via cloud-based technology, etc). How is this notion of social connectedness relevant to the treatment court field? It is hoped that the information presented in the multimedia resources featured here will encourage you to examine the ways in which your treatment court program facilitates meaningful social connection between and among participants, team members, and the recovery community through program requirements (e.g., case management sessions, pro-social activities, court review hearings, etc.). It is vital that opportunities for participants to connect with others are maintained.