Criminals. Offenders. Participants. People.: The Role of Our Beliefs in the Work of Treatment Courts

(This article is a part of the Connection: The Essential Practice for Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Treatment Courts series.)

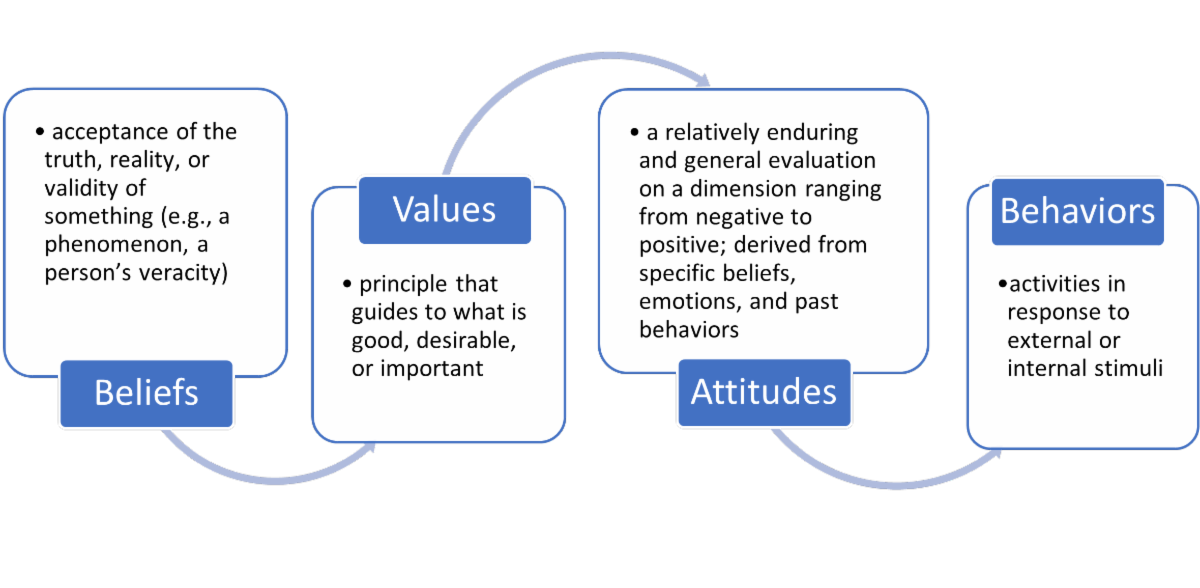

Connection is a through-line in the operating philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence. Yet, the anatomy of connection and that of therapeutic jurisprudence is complex, and precise roadmaps for either are debated among scholars. However, perhaps a helpful framing to best work toward living out this philosophy is to consider four elements: beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviors.

Source: American Psychological Association: https://dictionary.apa.org/

In the last article, the concept of mindfulness was introduced and defined as paying attention to what is happening in this moment, without judgement or reactivity to the thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations that arise (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). As we untangle the anatomy of therapeutic jurisprudence and connection, mindfulness practice allows you to notice what is happening in your mind and body. What thoughts, feelings, and sensations arise when you agree with an idea? When you disagree? Feel bored? When you dislike the idea, have unpleasant feelings, or uncover a judgment of yourself? The foundational skill of mindfulness invites you to stay curious about whatever comes up for you. Curiosity can make way for you to be kind towards yourself and – importantly – persistent in examining and reflecting upon the ideas ahead.

In unpacking the anatomy of connection and therapeutic jurisprudence, we will first focus on the role of beliefs.

Psychologists define beliefs as the “acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity of something, particularly in the absence of substantiation” (APA, 2022). Before we examine the role of beliefs in treatment court work, we must first familiarize ourselves with our own thoughts that are pertinent. You are invited to consider the following questions carefully and honestly:

- What thoughts arise when I think about people involved in the treatment court system?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about their motivation, wants, needs, behaviors, capacity for / interest in change, etc.

- What thoughts arise when I think about treatment courts?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about their purpose, design, utility, approach, effectiveness, etc.

- What thoughts arise when I think about my role in the treatment court system?

- It may be helpful to consider your ideas about your knowledge, skills, preparedness, attitude, motivation, capacity to provide support / make change, desire to help, resources, etc.

Now that you have begun unfolding your own thoughts, we will outline beliefs that therapeutic jurisprudence invites practitioners to try on in treatment court work. These beliefs can include:

- What do we believe about people involved in the treatment court system?

- All people have strengths, gifts, and talents.

- People are not their circumstances, conditions, experiences, or choices. People are in circumstances, experience conditions, have experiences, and make choices.

- People have a complex life story we know only a fraction about. It may include but is not limited to their involvement in the justice system.

- People have needs and wants as well as hopes for their lives.

- People are complex, and understanding them takes time, energy, and interest.

- People can change.

- People deserve support in their efforts to change.

- People will naturally make mistakes in the process of attempting to change their lives.

- All people regardless of identity or circumstance deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

- All people – regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, sexual identity, physical or mental disability, religion, or socioeconomic status deserve the same opportunities as other individuals to participate and succeed in treatment courts.

- What do we believe about treatment courts?

- The law can be leveraged to have a therapeutic effect, resulting in psychologically healthy outcomes.

- A collaborative, non-adversarial approach is most effective to supporting people to change their lives.

- Building relationships is necessary to positively impact treatment and court outcomes.

- The opportunity for alcohol and other drug treatment and mental health services can make a meaningful difference in people’s lives.

- What do we believe about practitioners’ roles in the treatment court system?

- The treatment court system works best with a connected, collaborative team.

- All members can learn from one another.

- All members of the multidisciplinary team bring a unique, necessary perspective and play an important role in participant outcomes.

- Transitioning to a team approach from an adversarial approach can take time, patience, and intention.

Why might honestly examining your own thoughts matter? Are your thoughts your actual beliefs? When do these automatic thoughts arise? Are the thoughts you had consistent with the beliefs outlined above? Where did your thoughts come from, and how might you challenge those that are inconsistent with those connected to therapeutic jurisprudence? Under what circumstances might your thoughts shift? (e.g., when you witness positive change, when your mood is low, when your body is activated, when your stress level is high, when you’re feeling really energized, etc.) And, when are you most generous thoughts about yourself around – when are the least generous ones pleasant?

Our beliefs about ourselves, others, and the world around us are deeply connected to our values, shape our attitudes, and influence our behavior—both personally and professionally.

In this way, we cannot solely focus on practitioners’ behaviors in cultivating a healthy, effective workforce. Yet, thoughts are not beliefs—unless we decide so.

We need to consider all aspects of the anatomy of therapeutic jurisprudence, starting with our actual beliefs about ourselves, others, and the work itself. Exploring our own thoughts means examining how we arrived at the ideas we have and the openness to challenges the ideas we hold. A part of the process also involves considering how our thoughts may automatically become beliefs without consciousness might affect our treatment of others.

Using the 5 A’s of mindfulness, you can distinguish thoughts from beliefs and uncover your actual beliefs with intentionality– a process that is critical to engaging skillfully and effectively in your work. For example, imagine you have thoughts that label those with whom you work as “offenders” and “criminals.” In using mindfulness, the following could unfold:

- Attention: intentional focus to the present moment:

- Noticing the labels of “offender” and “criminal” in your mind and conversations with colleagues

- Noticing judgmental thoughts about actions and choices of those involved in the treatment court system

- Noticing feelings of frustration, ambivalence, and an urge to disengage from helping

- Noticing sensations of agitation in the body

- Acceptance: recognition of the truth of what is happening in the mind and body (note: this is not resignation, simply acknowledging what is true at this time):

- “This is just what is happening right now – judgmental thoughts, frustrated feelings, and the urge to disengage.”

- Allowance: making space for the full experience of what is happening without pushing it away (unless it is skillful in the moment to have such boundaries)

- giving permission for what is happening in the mind and to exist—taking a moment to breath and avoid “busyness” that is sometimes deigned to move us away from what is really happening

- Attitude: bringing qualities of curiosity, non-judgment, openness, and kindness to witnessing and holding the inner experience

- “It’s interesting I’m having these thoughts; It’s understandable to have these thoughts – because I’m feeling extra stressed today, and this is the language that I hear all the time in society, too. All emotions are normal to feel.”

- Action: choosing deliberative responses (rather than automatic, habitual reactions) that are grounded in awareness of the present moment

- Reminding yourself that thoughts aren’t facts and do not have to be representative of your actual beliefs because they arose in your mind. Our beliefs are our choices.

- Reminding yourself that labels like “offender” and “criminal” are reductionistic, diminishing of someone’s humanity, and disconnecting; they are problematic because they label the entire person by a behavior and make us feel far and separate from that person (i.e., disconnected)

- Choosing to reframe that language in your mind in speech—maybe even by simply thinking about the person by their name, dropping the label altogether. (i.e., Sam experienced a substance use relapse versus An offender in the program relapsed.)

- Taking care of yourself in the best way for you in response to the frustration/agitation that is around and possibly connected to automaticity of labeling (e.g., talking with a supervisor about a challenging interaction with the person)

- Taking a step to reconnect to that person, even if only in your mind and body (e.g., think of one thing you have in common with that person)

Thoughts are only mental experiences that we often mistake as facts or chosen beliefs; however, we can choose to buy into our thoughts or not. Beliefs are, in fact, choices. Bringing more consciousness to the ways in which with think about ourselves, others, and work positions us to stay connected—to ourselves, to others, and to our professional values, attitudes, and behaviors.

What we choose to believe directly impacts how we engage. How we engage directly impacts the lives of others.

And, we want to engage with the belief that those in the treatment court system are, in fact, criminals, offenders, participants people.

A Connection Call to Action:

This week, you are invited to engage in a connection call to action to try out the ideas discussed.

Connecting with yourself:

Examine your beliefs about yourself, focusing on your strengths. Take a few moments each day to make a list of 5 of the strengths you demonstrate in your work.

Connecting with others:

Examine your beliefs about those in a participant role, focusing on identifying their strengths. Take a few moments each day to make a list of 5 of the strengths you see in a person with whom you are / were working. Each day, choose a new person to think about. You are especially encouraged to focus on those people who brought up feelings of frustration for you or with whom you have / had a strained working relationship.

References:

American Psychological Association. (2022, April 1). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2018). Falling awake: How to practice mindfulness in everyday life. Hachette UK.

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of psychosomatic research, 78(6), 519-528.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932-932.

Lee, J. J. (2021, May). Education for Emotional Rigor: The Pedagogy of Mindful Self-Care. Presented (oral presentation) at International Teaching and Learning Cooperative (ITLC): Lilly Online Conference. Virtual.

Lee, J. J. (2020, September). What’s in Your Backpack?: Mindful Self-care and Emotional Rigor of a Crisis. The New Social Worker. https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/practice/your-backpack-mindful-self-care-emotional-rigor-covid19-crisis/

Visted, E., Vøllestad, J., Nielsen, M. B., & Nielsen, G. H. (2015). The impact of group-based mindfulness training on self-reported mindfulness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(3), 501-522.

Written by Jacquelyn Lee, Ph.D., LCSW

Associate Professor, School of Social Work, UNCW